Try yourself:

Register a face and try liveness verification at www.jchowlabs.me.

Face Verification System Internals

In this article, we’re going to look under the hood of facial verification system. The goal is to develop stronger intuition for how modern facial recognition systems work from the moment you capture a face to the moment a system decides whether to grant access. We’ll walk through the core pieces step by step so you can see how they fit together as a coherent system rather than a black box.

Facial recognition is now woven into everyday digital life. We use it to unlock our phones, sign into applications, pass through secure facilities, verify our identity for financial services, and recover accounts when we’ve lost access. To users, these experiences often feel effortless, but behind that simplicity sits a carefully engineered pipeline that must work across different lighting conditions, camera qualities, poses, and real-world noise while also resisting spoofing and fraud. As facial recognition becomes a gateway to increasingly sensitive systems, including those that hold financial, medical, and corporate data, it’s important to understand not just that it works, but how it works.

In the sections that follow, we’ll break the facial recognition system into its major components. We’ll start with how faces are captured, detected, and aligned. Then we’ll look at how modern systems convert faces into mathematical embeddings, how those embeddings are compared and stored, and how thresholds and policies turn similarity scores into real access decisions. Finally, we’ll examine liveness detection and deepfake defenses as critical layers that sit around the core verification pipeline.

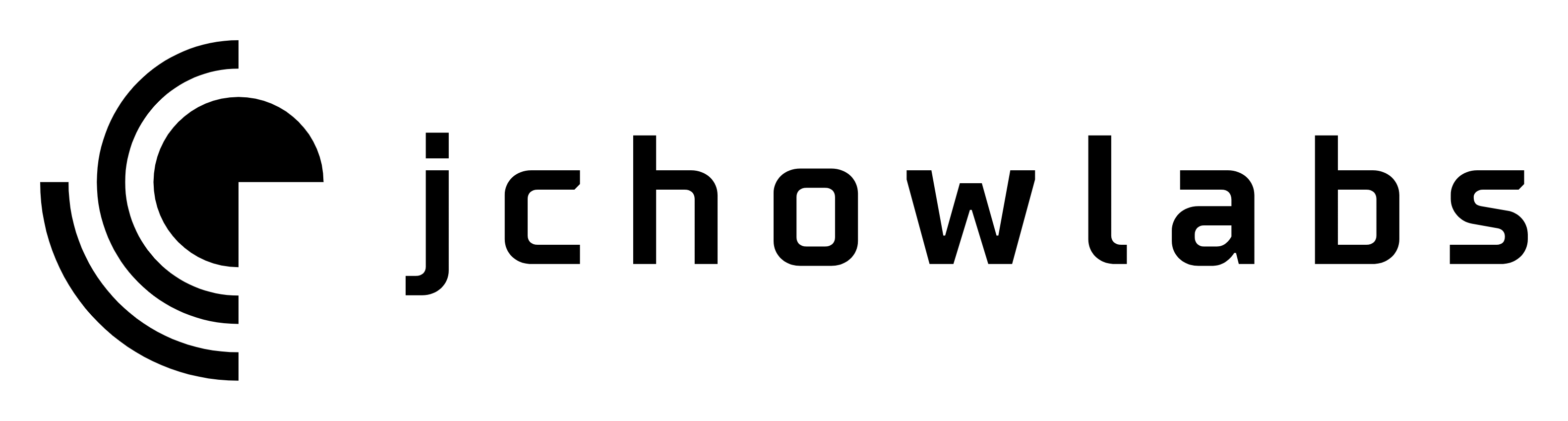

The Facial Recognition Pipeline

At its core, a facial recognition system is best understood not as a single model or algorithm, but as a pipeline that transforms raw visual input into an identity decision. Different vendors implement this pipeline in different ways, but most modern systems share the same basic structure. Thinking in terms of layers makes the overall system much easier to reason about, especially from a security or architecture perspective.

You can think of the pipeline as moving through five broad stages:

1. Capture

A camera collects an image or short video of a person’s face. This might be a smartphone selfie camera, a laptop webcam, or a dedicated sensor in a kiosk or access control device. Even this first step is nontrivial, since real-world environments vary widely in lighting, movement, and positioning.

2. Face Detection and Alignment

Once an image is captured, the system must determine whether a face is present and where it is located. Detection models scan the image and draw bounding boxes around regions that likely contain faces. If a face is found, alignment routines rotate, crop, and normalize it so that key landmarks like the eyes, nose, and mouth appear in consistent positions. This produces a standardized “face chip” that downstream models can work with reliably.

3. Representation, or Embedding Generation

Rather than storing or comparing images directly, modern systems pass the aligned face through a neural network that converts it into a compact numerical vector called an embedding. This embedding captures distinctive features of the face in high-dimensional space while filtering out irrelevant details like background or lighting. At this point, the system is no longer dealing with pictures, but with numbers.

4. Matching

The new face embedding is then compared against stored references. In a verification scenario, the system compares it to a single enrolled embedding for the claimed user. In an identification scenario, the system searches across many stored embeddings to find the closest match. Similarity is measured using distance metrics rather than visual inspection.

5. Decision and Policy

Finally, the system applies thresholds and business logic to decide what to do. If the similarity score is high enough, access may be granted. If it is borderline, the system might request additional proof, such as a second biometric or a passcode. If it is too low, access is denied. In many real systems, this decision is also informed by contextual signals like device trust, location, or recent behavior.

If you zoom out, these five stages naturally divide into two conceptual halves.

The first half is perception and representation. This includes everything from camera capture through face detection, alignment, and embedding generation. Its job is to reliably convert messy real-world images into clean, comparable data.

The second half is identity reasoning. This includes matching, thresholding, and decision-making. Its job is to interpret the embedding in the context of stored identities and security policy.

These two halves are tightly coupled. Better detection and embeddings make matching easier and more reliable. Smarter decision policies reduce false positives and false negatives. Together, they form the backbone of modern facial recognition systems.

In the next section, we will zoom in on the first part of this pipeline and look more closely at how systems actually capture, detect, and normalize faces before any recognition even begins.

Face Capture & Detection

Before any facial recognition can happen, a system has to solve a surprisingly difficult problem: turning a messy, real-world image into a clean, standardized face that a model can reason about. This step often receives less attention than machine learning, but in practice it is one of the most important parts of the entire system. If the input is poor, everything that follows will be unreliable.

Capturing the face

The pipeline begins with a camera. Depending on the use case, this might be a smartphone selfie camera, a laptop webcam, or a dedicated sensor in a kiosk, door reader, or airport gate. Many systems capture short video rather than a single photo, because multiple frames provide more information and make it easier to select a high-quality image.

From a user’s perspective, this stage often includes simple guidance prompts such as:

- “Center your face in the frame.”

- “Move closer to the camera.”

- “Improve your lighting.”

- “Turn your head slightly.”

These prompts are not cosmetic. They are part of the system’s attempt to reduce variability before any machine learning runs. Better lighting, clearer positioning, and steadier movement all increase the chance that downstream steps will work correctly.

Behind the scenes, systems may also apply lightweight preprocessing such as adjusting brightness, reducing noise, or selecting the best frame from a short video clip. The goal is to give the detection model the cleanest possible starting point.

Detecting the face

Once an image is captured, the system must answer a basic but critical question: is there a face here, and where is it?

This is the job of face detection. A detection model scans the image and draws one or more bounding boxes around regions that likely contain faces. In crowded scenes, it may find multiple faces, in which case the system must decide which one to focus on. In other situations, it may fail to find any face at all, triggering a recapture request.

Detection also has to work across a wide range of real-world conditions. Faces may be partially obscured by glasses, hair, hats, or masks. They may be turned sideways, tilted, or far from the camera. Modern detectors are trained to handle this variability, but their performance still depends heavily on image quality from the capture step.

Aligning and normalizing the face

Finding a face is not enough. Different people present their faces at different angles, distances, and orientations. To make recognition reliable, systems must standardize what the face looks like before further processing.

This is where alignment comes in. The system identifies key facial landmarks such as the eyes, nose, mouth, and chin. Using these reference points, it can:

- Rotate the face so the eyes are level.

- Crop out everything except the facial region.

- Scale the face to a consistent size.

The result is often called a “face chip” — a normalized, tightly cropped image of just the face in a standard format. This removes much of the variability that would otherwise confuse downstream models.

Why this stage matters

You can think of capture, detection, and alignment as the data engineering layer of facial recognition. They do not determine identity directly, but they shape everything that follows.

If lighting is poor, the face is misaligned, or the wrong region is cropped, the system may generate a bad representation of the person even if the recognition model itself is excellent. In that sense, many real-world failures of facial recognition are not failures of “AI,” but failures of getting clean, consistent input.

Once this stage is complete, the system has a standardized, well-framed image of a single face. At that point, the problem shifts from “where is the face?” to “who is this person?” — which is where we turn next.

In the following section, we’ll look at how modern systems convert this normalized face into a mathematical representation known as an embedding.

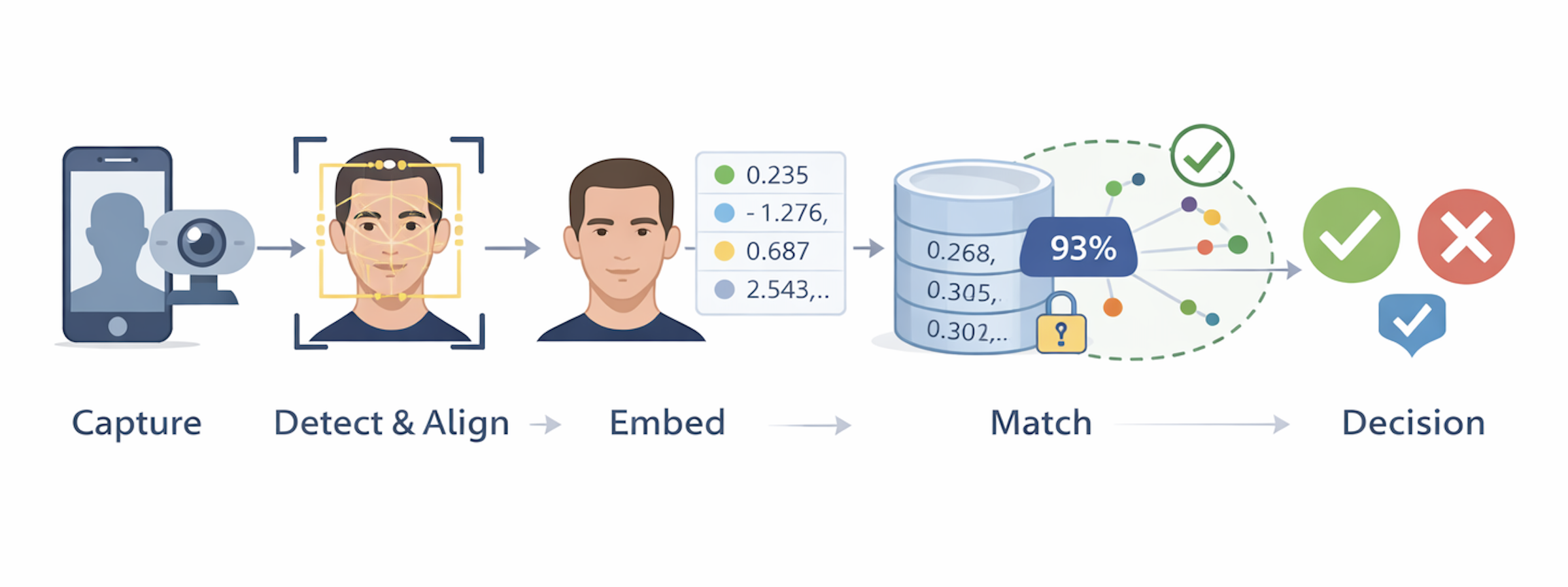

Face Embeddings — Turning Faces into Numbers

Once a face has been detected, aligned, and normalized, the system is ready for the step that makes modern facial recognition fundamentally different from older approaches: converting the image into a numerical representation known as a face embedding.

At a high level, an embedding is a compact mathematical summary of a face. Instead of treating the face as a grid of pixels, the system passes the aligned image through a neural network trained on millions of examples of faces. That network distills what it has learned about facial structure into a fixed-length vector of numbers. Depending on the model, this vector might have 128, 256, or 512 dimensions, but regardless of size, its purpose is the same: to represent identity in a form that is easy to compare.

Importantly, this embedding does not look like a face, and it is not meant to be interpretable by humans. There is no single number that corresponds to “nose shape” or “eye spacing.” Instead, identity is encoded across many dimensions simultaneously. The power of this approach is that the network learns to emphasize features that are stable across lighting, pose, and expression, while downplaying details that are irrelevant to who the person is.

A helpful way to think about embeddings is as points in an abstract “face space.” Every person corresponds to a cluster of points in this space rather than a single image. Photos of the same person taken under different conditions should land close together, while photos of different people should fall far apart. Recognition then becomes a geometric problem: measure how close two points are and decide whether they are likely to represent the same individual.

This approach is a major departure from older, handcrafted methods that relied on manually designed features such as edge patterns or texture histograms. Those techniques could work in controlled settings but struggled in the real world. Modern embedding models learn directly from data, which allows them to generalize much better across cameras, environments, and demographics.

Embeddings also serve several practical purposes in real systems. They are compact compared to storing raw images, which makes storage and search more efficient. They make comparison fast and consistent, since distance between two vectors is much easier to compute than pixel-by-pixel image similarity. And while embeddings are still sensitive biometric data, they provide some separation between the original image and the identity representation, which can be useful in privacy-conscious system designs when handled carefully.

By the time this step is complete, the system is no longer dealing with pictures at all. The face has been reduced to a point in high-dimensional space that captures “who this person is” in mathematical form. The next challenge is to decide what to do with that point.

In the following section, we’ll look at how systems compare embeddings, choose thresholds, and ultimately decide whether two faces should be treated as the same person.

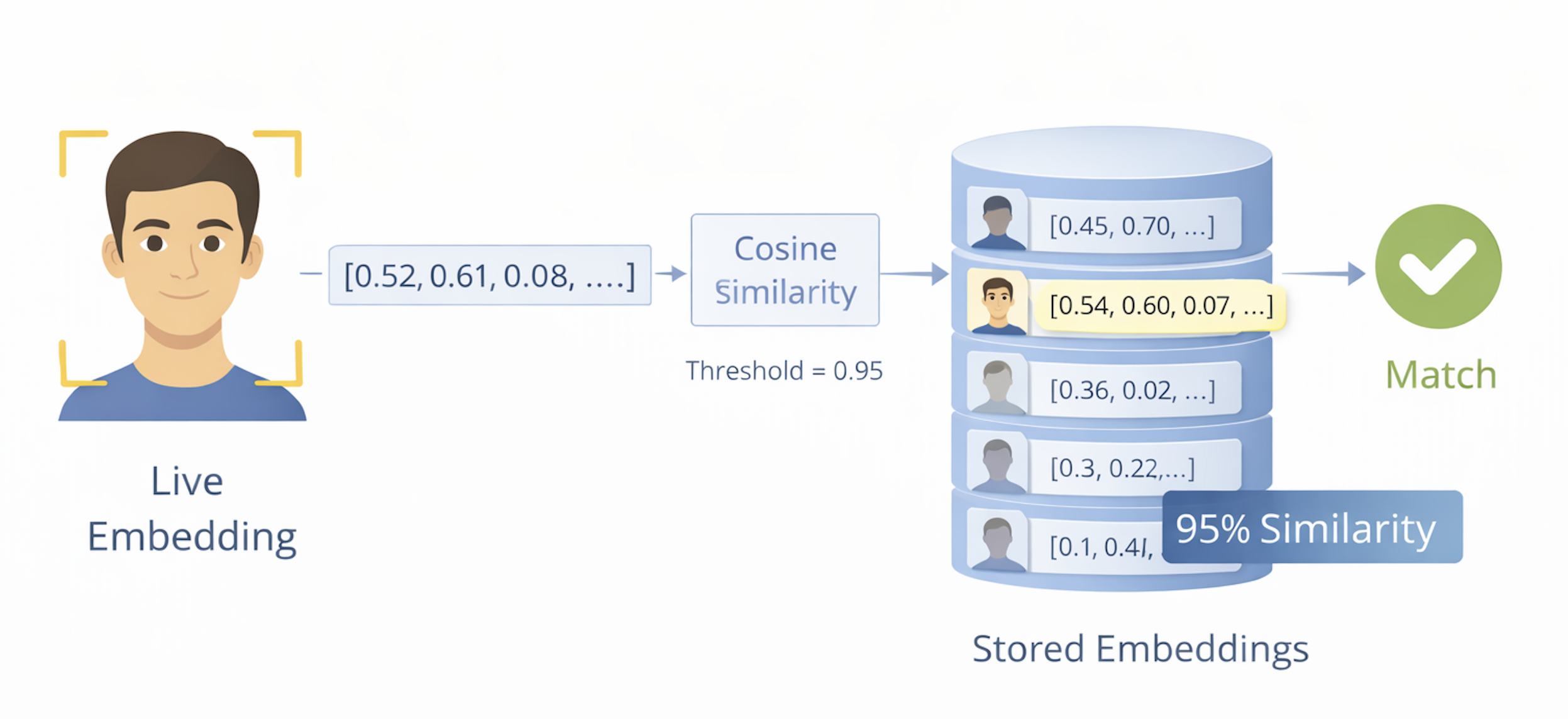

Similarity & Matching

Once a face has been converted into an embedding, the problem of recognition becomes a problem of comparison. The system is no longer asking “what does this face look like?” but rather “how similar is this new embedding to the ones we already have?” This is where statistics meet identity policy.

Comparing embeddings

Every enrolled person in the system is represented by one or more stored embeddings. When a new face is captured, the system generates a fresh embedding and compares it to those stored references.

Rather than comparing images directly, the system measures distance between two vectors. There are several ways to do this in practice, but conceptually they all answer the same question: how far apart are these two points in face space?

- If the distance is small, the faces are likely to be the same person.

- If the distance is large, they are likely different people.

You can think of this like proximity on a map. Two cities that are close together are likely in the same region; two that are far apart are almost certainly in different ones. The system uses the same intuition, just in a high-dimensional space instead of a geographic one.

Thresholds turn similarity into a decision

Distance alone does not produce an answer. To make a real identity decision, the system applies a threshold.

If the similarity score is above the threshold, the system treats the faces as a match. If it falls below, the system rejects the match.

Choosing this threshold is one of the most important design decisions in any facial verification system, and it is fundamentally a policy choice, not a technical one. It determines how the system balances two types of error:

- False acceptance: the system mistakenly treats two different people as the same.

- False rejection: the system mistakenly blocks the real user.

A strict threshold reduces fraud but creates more friction for legitimate users. A looser threshold makes the system feel smoother but increases risk. Real systems tune this setting differently depending on context. Unlocking a phone might tolerate more leniency than authorizing a wire transfer at a bank.

Verification versus identification

At this point, it helps to distinguish two related but very different use cases.

In verification (1:1), the user claims an identity, and the system checks that claim. For example, “I am Alice.” The system compares the live embedding only against Alice’s enrolled embedding. This is fast, controlled, and generally safer.

In identification (1:N), the system tries to determine who the person is without a claim. It compares the live embedding against many stored embeddings and looks for the closest match. This is computationally harder, raises more privacy concerns, and carries a higher risk of false positives at scale.

The underlying technology is the same, but the implications are very different.

Context shapes the final decision

Most real systems do not rely on face similarity alone. The matching score is combined with additional context before granting access.

For example, the system might consider:

- Whether the request comes from a trusted device.

- Where the user is located.

- Whether recent behavior looks normal.

- Whether the attempt is part of a suspicious pattern.

If the face match is strong but the context looks risky, the system might require a second factor such as a passcode. If the face match is borderline but everything else looks normal, it might allow access with minimal friction.

In this way, facial recognition becomes one signal in a broader identity decision rather than the sole authority.

Liveness Detection

Up to this point, we have described how a system captures a face, turns it into an embedding, and compares that embedding to decide whether two faces match. This is the heart of facial recognition. But there is an important gap in that story. A system could perform all of those steps perfectly and still be fooled by a photograph, a video, or a synthetic image. That is where liveness detection comes in.

Liveness detection is not about recognizing who a person is. It is about answering a different question: is this a real, physically present person right now? Recognition answers “is this the same face?” while liveness answers “is this a living person in front of the camera?”

Most modern facial verification systems treat liveness as a separate but tightly coupled layer that sits around the core recognition pipeline. Typically, it is applied after a face is detected but before a final match is accepted. If the system cannot establish liveness, it will refuse to proceed regardless of how similar the face looks to the enrolled identity.

There are several common approaches to liveness detection, and real systems often combine more than one.

One approach relies on user interaction challenges. The system may ask the person to blink, smile, turn their head, or follow a dot on the screen. These small, spontaneous movements are difficult to convincingly reproduce with a static photo and harder to perfectly mimic with a pre-recorded video.

Another approach looks for physical depth cues. A real face has three-dimensional structure, while a printed photo or a flat screen does not. Some devices use infrared sensors, structured light, or stereo cameras to detect depth and ensure that the face occupies a real volume in space rather than lying flat on a surface.

A third class of techniques analyzes temporal behavior in video. Instead of relying on a single frame, the system watches how the face moves over time, looking for subtle patterns in motion, texture, and lighting that are characteristic of living skin and natural movement.

From a system perspective, liveness serves two main purposes. First, it reduces the risk that someone can simply hold up a photo of another person and gain access. Second, it raises the bar for more sophisticated attacks, such as using high-quality video replays or digital manipulation.

However, liveness detection is not a silver bullet. Attackers continuously develop new ways to mimic or simulate human presence, and defenses must evolve in response. In practice, liveness is best thought of as a risk mitigation layer rather than a perfect guarantee.

It is also important to note that liveness does not replace identity verification. A system could confirm that a real person is present and still get their identity wrong. The two checks work together: liveness establishes presence, while facial recognition establishes identity.

In the next section, we will look at a related but more modern challenge: deepfakes.

Deepfakes — A New Class of Spoofing Risk

Even with solid liveness detection in place, modern facial verification systems face a newer and more subtle challenge: deepfakes. Whereas traditional spoofing relies on physical artifacts like photos, masks, or replayed videos, deepfakes use generative AI to create or manipulate facial imagery that can look strikingly realistic.

At a high level, a deepfake is synthetic media that convincingly imitates a real person’s appearance, movement, or expressions. In the context of facial recognition, this could mean a video that appears to show a real individual speaking, blinking, and moving naturally, even though it is entirely computer-generated or heavily altered. Unlike a static photo, a deepfake can pass many simple motion-based checks.

From a system design perspective, deepfakes blur the boundary between “real presence” and “convincing imitation.” A face might look three-dimensional, move fluidly, and respond to prompts, yet still not correspond to a real person in front of the camera.

To defend against this, modern systems layer additional safeguards on top of both recognition and liveness. These defenses tend to fall into three broad categories.

First, many systems use media forensics techniques that analyze the video itself for subtle inconsistencies such as unnatural lighting patterns, irregular skin textures, or frame-to-frame artifacts.

Second, some systems incorporate adversarially trained models that have been exposed to large numbers of deepfake examples, teaching them to recognize systematic patterns of synthetic media.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, systems increasingly avoid relying on face alone. They combine facial signals with device, behavioral, and contextual evidence, such as whether the camera sensor appears genuine or whether the session originates from a trusted device.

Despite these defenses, deepfake technology is improving rapidly, and detection methods are constantly playing catch-up. There is no single test that can permanently solve the problem. Instead, deepfake resistance is best viewed as an ongoing arms race.

In practice, this means that deepfake safeguards should be treated as part of a continuously evolving security layer around the core facial verification pipeline.

Closing

If you step back, a facial verification system is less about a single clever algorithm and more about a sequence of coordinated design choices. It begins with the messy reality of image capture and the practical work of detecting and aligning a face. It then translates that face into a mathematical embedding that can be stored, compared, and reasoned about at scale. Around that core sit matching policies, storage decisions, and security controls that determine how the technology is actually used in the real world.

Seen this way, the system follows a consistent logic: capture, normalize, represent, compare, and decide. Liveness detection and deepfake defenses do not replace this pipeline; they surround it as protective layers that reduce the risk of spoofing and manipulation. Thresholds and context do not change what the model computes; they shape how organizations choose to act on its output.

Thinking in these terms makes facial recognition easier to understand and easier to evaluate. You can ask clearer questions about where data lives, how errors are handled, who bears the risk of a mistake, and what happens when an attack succeeds. Those are the same questions a security architect would ask of any critical identity system.

Ultimately, building intuition about facial recognition is less about mastering machine learning and more about recognizing how its components fit together as a system. Once you can see that structure, facial recognition stops feeling like magic and starts looking like what it really is: a layered piece of identity infrastructure with real strengths, real limits, and real tradeoffs.