Reconstructing Biometric Data

Biometrics have quietly become one of the most important primitives in modern digital identity systems. Faces unlock phones, authorize payments, approve remote onboarding, and increasingly serve as proof that a human — and a specific human — is present behind a transaction. Fingerprints, voice, iris patterns, and behavioral signals are now routinely used to replace or augment passwords, tokens, and shared secrets.

This shift is not accidental. Password-based authentication has proven fragile at scale. Phishing, credential stuffing, replay attacks, and large-scale data breaches have eroded trust in knowledge-based authentication. Biometrics promise something different: authentication rooted in the body itself. You do not remember your face. You do not type your fingerprint. You simply present who you are.

Embedded in this promise is a powerful assumption: that biometric data, once captured and transformed by a system, cannot be meaningfully reversed or reused by an attacker. In popular imagination, biometric enrollment is often understood as little more than "taking a picture" or "scanning a finger" and storing it securely. If the original image is never stored, and only some abstract representation remains, surely that representation must be safe.

That assumption is increasingly incorrect.

Modern biometric systems do not merely compress images. They extract dense, numerical representations designed to preserve identity with high fidelity. At the same time, advances in generative modeling have made it possible to synthesize realistic biometric artifacts from abstract representations. The intersection of these two trends has given rise to biometric template inversion attacks: techniques that reconstruct biometric data — or data functionally equivalent to it — from the internal representations used by verification systems.

Understanding these attacks is no longer an academic exercise. As biometrics are used more widely to establish identity across the internet, including in environments where deepfakes and synthetic media are already eroding trust, the ability to reconstruct or impersonate biometric identity becomes a systemic risk. This article explores how biometric verification systems actually work, why inversion attacks are possible, how they are carried out in practice, and what this means for anyone building or selecting identity verification technology today.

How Biometric Verification Systems Actually Work

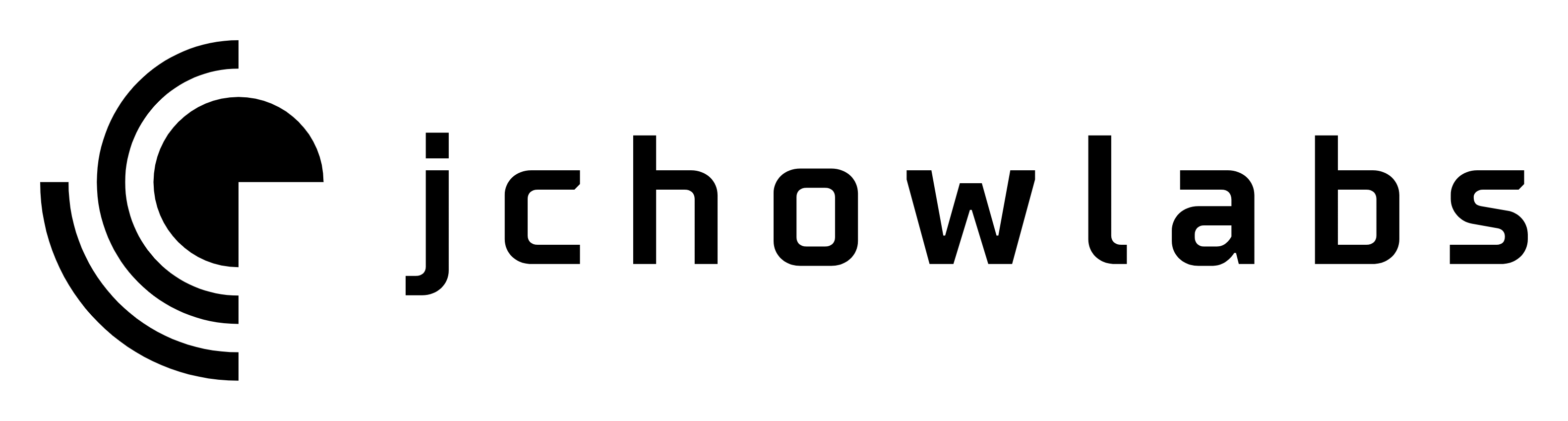

To understand biometric inversion, it is essential to first understand how biometric verification systems operate beyond the surface-level intuition. Enrollment is not simply the act of capturing and storing an image, nor is authentication merely a comparison of pictures. The core of modern biometric systems lies in numerical representation and geometric comparison.

During enrollment, a biometric sensor captures raw data. In the case of facial recognition, this may be a single image, a short video sequence, or a set of frames under different poses or lighting conditions. For fingerprints, it may be an optical, capacitive, or ultrasonic scan. This raw data is not stored directly. Instead, it is processed by a feature extraction model, almost always a deep neural network trained to encode identity-relevant information.

The output of this model is a biometric template: a vector of real-valued numbers, often hundreds of dimensions in length. This template is designed such that two samples from the same individual produce vectors that are close to one another in the embedding space, while samples from different individuals are far apart. The precise notion of "close" depends on the similarity or distance metric used by the system, but the underlying objective is the same across modalities.

What matters is that this template is not arbitrary. It is a structured, learned representation that preserves aspects of the biometric signal that are predictive of identity. In effect, it is a compressed encoding of who you are, optimized for comparison rather than reconstruction.

During authentication, the process repeats. A new biometric sample is captured, passed through the same feature extractor, and transformed into a new template. The system then computes a similarity score or distance between the newly generated template and the enrolled one. If this score exceeds a predefined threshold — chosen to balance false accept and false reject rates — the system grants access.

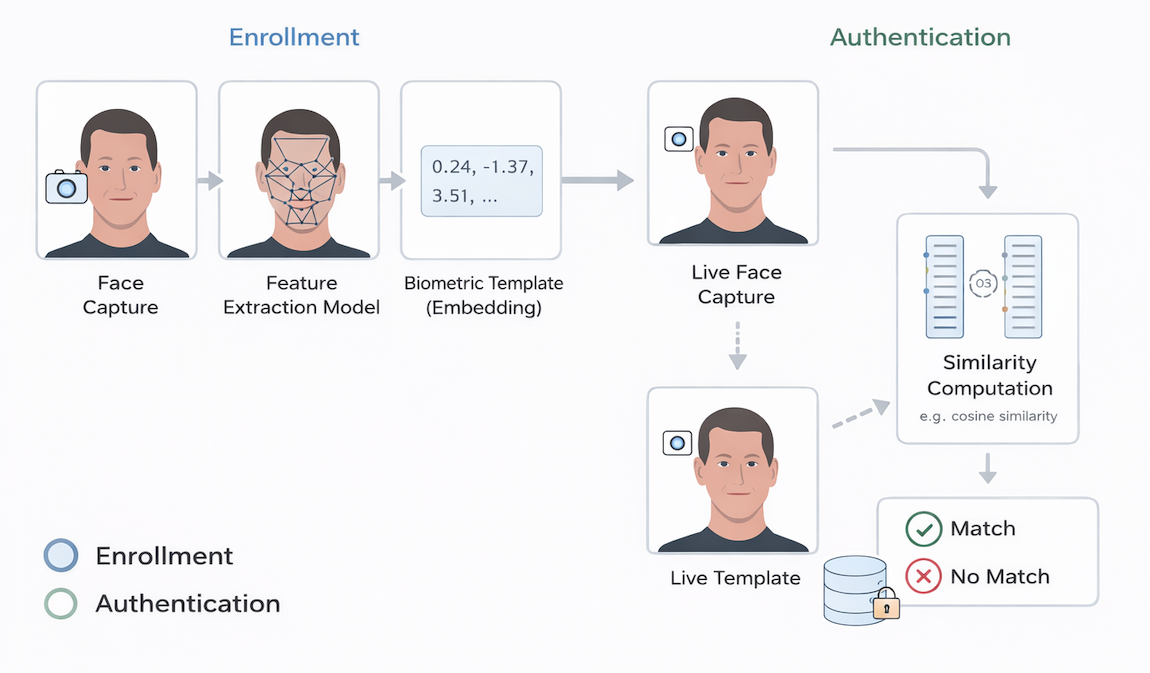

This process defines a decision rule in the embedding space. For each enrolled user, there exists a region of templates that will be accepted as belonging to that user. Whether explicitly modeled or not, this region has a geometric structure. It is this structure — not the original image or scan — that ultimately governs authentication decisions.

A critical implication follows from this design: authentication systems leak information about the relationship between input samples and stored templates. Every similarity score, every accept or reject decision, reflects something about the position of the probe template relative to the enrolled template. Over time, and with sufficient interaction, this information can be exploited.

Biometric Templates as Numerical Identity Representations

A common misconception about biometric systems is that once a biometric image is converted into a template, the original information is effectively destroyed. In reality, modern templates are not lossy in the way cryptographic hashes are lossy. They are designed to preserve identity-relevant structure, and that structure is precisely what makes them useful — and vulnerable.

Deep learning–based biometric embeddings encode information about facial geometry, texture, spatial relationships, and other latent attributes. While they may discard irrelevant details such as background or lighting conditions, they retain enough structure to reliably cluster samples from the same individual across a wide range of conditions. This implies that templates must contain a rich representation of identity.

From a mathematical perspective, biometric templates occupy a high-dimensional space in which distance corresponds to similarity of identity. This space is not random. It is shaped by the training data, the loss function, and the inductive biases of the model architecture. Identities form clusters, and variations such as pose or expression trace out smooth trajectories within those clusters.

Importantly, many different biometric samples may map to templates that are sufficiently close to one another to be considered equivalent by the matcher. This one-to-many mapping is often cited as a reason inversion should be difficult. In practice, it has the opposite effect. If many inputs are acceptable, an attacker does not need to recover the original biometric — only one valid preimage that falls within the acceptance region.

This distinction underpins most modern inversion attacks. The goal is not perfect reconstruction, but functional impersonation.

What Is a Biometric Template Inversion Attack?

A biometric template inversion attack seeks to reverse the biometric verification pipeline, either partially or fully. Instead of starting with a biometric sample and producing a decision, the attacker starts with information exposed by the system — templates, similarity scores, or binary decisions — and works backward to recover identity-bearing artifacts.

Inversion attacks can be categorized by what information the attacker has access to and what they aim to recover. In some cases, the attacker obtains stored biometric templates directly, perhaps through a database breach, insider access, or compromised endpoint. In other cases, the attacker has no access to stored templates but can interact with the authentication system and observe its responses.

The attacker's objective may be to reconstruct a biometric template numerically, to generate a biometric sample that embeds to that template, or both. In either case, success is measured not by visual similarity to the original biometric, but by the ability to authenticate as the target user.

This is a subtle but crucial point. In biometric systems, authenticity is defined operationally by the matcher. If a reconstructed artifact passes the matcher's threshold, it is, for all practical purposes, equivalent to the original biometric. The system itself cannot distinguish between them.

How Template Reconstruction Attacks Work

Template reconstruction attacks focus on recovering the numerical representation used internally by the system. These attacks exploit the fact that matching behavior reveals information about distances or similarities in embedding space.

When a system returns similarity scores, the attack surface is particularly large. Each query provides a numerical relationship between the probe template and the unknown enrolled template. Over many queries, these relationships can be combined to infer the position of the enrolled template in the embedding space. In effect, the system becomes a measurement device that allows the attacker to triangulate the target template.

Even when systems do not expose scores, binary decisions still leak information. An accept or reject response answers a geometric question: is the probe template inside or outside the acceptance region? By carefully crafting probes and observing these responses, an attacker can approximate the boundary of that region. With enough boundary points, the center of the region — corresponding to the enrolled template — can be inferred.

What makes these attacks particularly concerning is that they do not require knowledge of the matching threshold, the distance metric, or the internal parameters of the model. They rely only on the consistency of the decision rule and the ability to query the system repeatedly. In practice, many production systems satisfy these conditions.

Once a template has been reconstructed, it can often be reused indefinitely, injected into downstream systems, or used as a target for further reconstruction attacks.

From Template Reconstruction to Biometric Replay

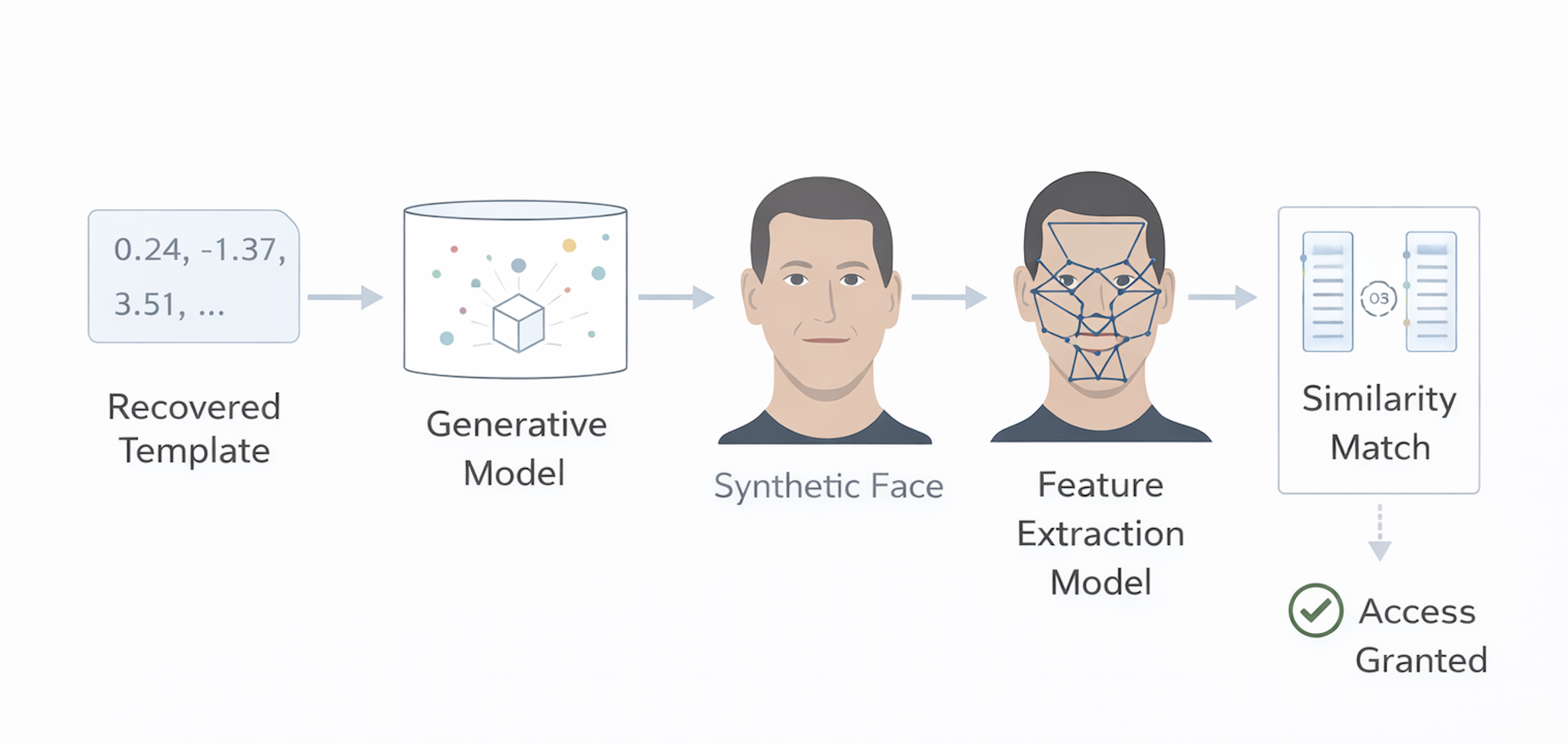

Recovering a template is often only a stepping stone. The more operationally dangerous attacks are those that convert reconstructed templates into biometric samples that can be presented to the system.

This is where advances in generative modeling play a decisive role. Modern generative models can synthesize faces, fingerprints, and other biometric artifacts conditioned on abstract representations. By learning a mapping from biometric embedding space to the latent space of a generator, an attacker can produce images that, when processed by the feature extractor, yield templates close to the target.

For facial recognition systems, this process can be further enhanced by exploiting pose, expression, and camera parameters. Three-dimensional or pose-aware generators allow attackers to search for presentations that maximize match scores, effectively optimizing not just the face itself, but how it is shown to the system.

Importantly, these reconstructed samples do not need to be perfect. They need only to survive the feature extraction and matching stages. Any visual artifacts that are not penalized by the embedding model are irrelevant to the attack's success.

In the context of fingerprints, reconstructed minutiae patterns can be rendered into images or physical artifacts suitable for presentation attacks. The details differ, but the principle remains the same: if the internal representation can be inferred, a usable external artifact can often be synthesized.

Why These Attacks Are Increasingly Practical

Biometric inversion attacks are not theoretical curiosities. Their practicality has increased for several reasons.

First, biometric systems are deployed at unprecedented scale, often over network-accessible interfaces. This increases the likelihood of oracle access and makes large numbers of queries feasible.

Second, biometric embeddings have become more standardized and transferable. Models trained for recognition share similar inductive biases, making cross-system attacks increasingly viable.

Third, generative AI has dramatically reduced the cost and expertise required to synthesize convincing biometric data. What once required bespoke modeling now benefits from large pretrained models and foundation architectures.

Finally, biometrics are increasingly used in high-stakes contexts: remote onboarding, financial authorization, access to critical systems. The incentive to attack these systems is growing accordingly.

Implications for Digital Identity in an AI-Driven World

Biometric inversion attacks intersect directly with broader concerns about digital identity and synthetic media. As deepfakes blur the line between real and generated content, biometrics are often proposed as a way to anchor identity in physical reality. Yet biometric systems themselves rely on representations that can be learned, modeled, and exploited.

If biometric data can be reconstructed or impersonated, then identity verification systems that rely heavily on biometrics risk becoming vulnerable to the very automation they are meant to resist. This does not render biometrics useless, but it does require a more nuanced understanding of their limitations.

Biometrics should not be treated as secrets. They are identifiers, not keys. Once compromised, they cannot be rotated in the same way as passwords or cryptographic credentials. This makes template inversion particularly dangerous, as it threatens the long-term integrity of identity systems.

Designing and Selecting Biometric Systems with Inversion in Mind

The reality of template inversion attacks has implications both for those building biometric systems and for those selecting them.

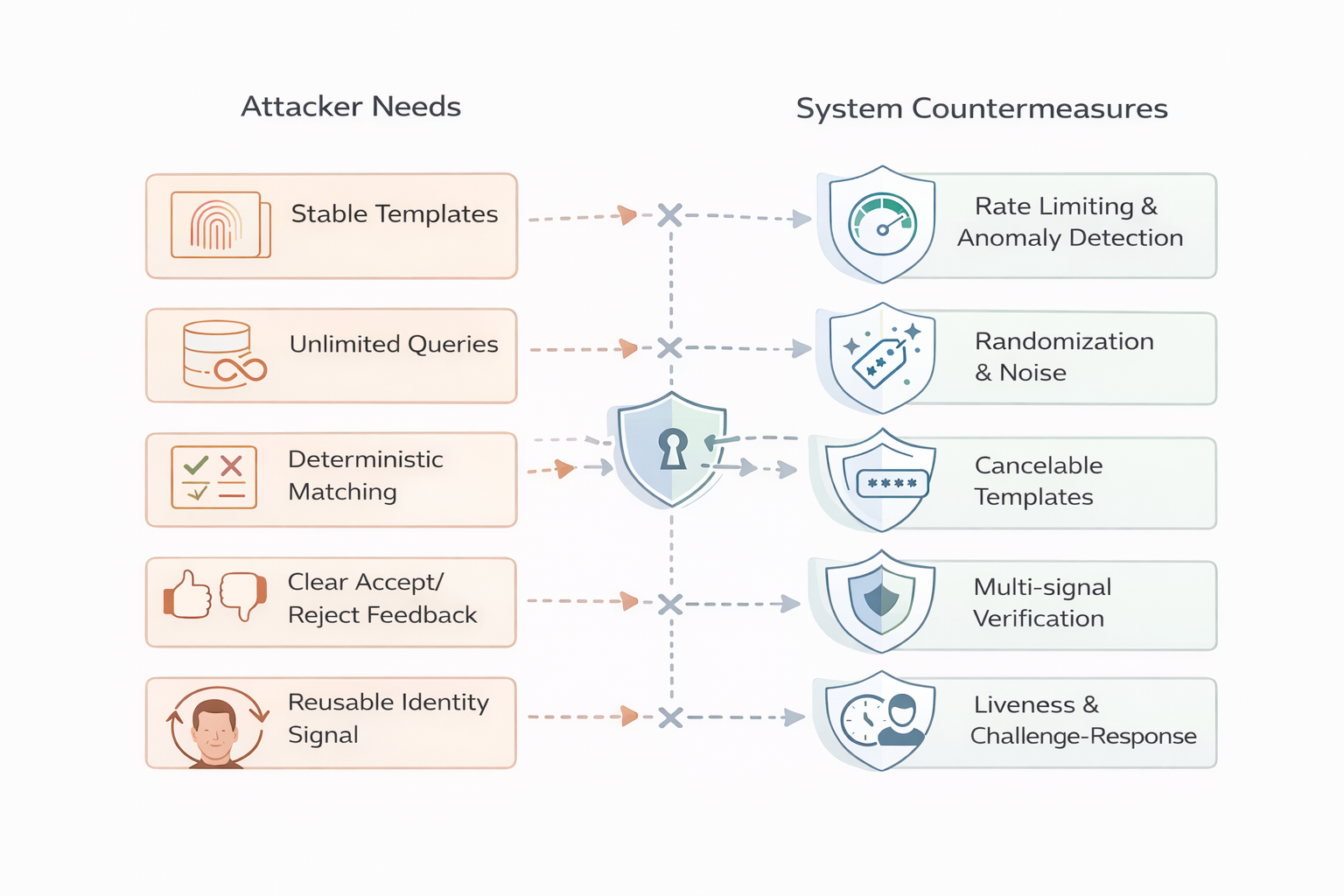

For system designers, the lesson is that inversion must be considered a first-class threat. Assumptions about template secrecy, limited attacker interaction, or irreversibility are no longer safe. Systems should be designed to limit oracle leakage, restrict query behavior, and minimize the consequences of template compromise. Biometric signals should be layered with other forms of authentication and verification, rather than treated as a root of trust.

For buyers of biometric solutions, the challenge is asking the right questions. How are templates generated and stored? Are they deterministic or randomized? What feedback does the system expose during authentication? How does it detect and respond to abnormal querying behavior? Can templates be revoked or transformed if compromised? A vendor's ability to answer these questions transparently is a meaningful indicator of system maturity.

Closing

Biometric template inversion attacks force a reexamination of how we think about identity, authenticity, and trust in digital systems. They demonstrate that the internal representations used by biometric systems are not opaque or one-way, but structured and learnable. As AI continues to advance, the gap between recognition and reconstruction will only narrow.

This does not mean biometrics should be abandoned. It means they must be understood — deeply and realistically — as part of a broader security architecture. The question is not whether biometric data can be reconstructed. The question is whether our systems remain trustworthy when it is.